BMW Art Guide by Independent Collectors

An Eye into a Secret World

SIP Shpilman Institute for Photography – Tel Aviv, Israel

On the third floor of an old industrial building in South Tel Aviv there is a heavy door with a narrow window in it. Behind it is the Shpilman Institute for Photography (SIP). The SIP is focused on work that breaks from a documentary approach to photography and plays with its artistic qualities.

Vered Snear, an artist and researcher at the museum, has offered to guide me through their exhibition of surrealist photography from the early twentieth century: "The Naked Eye." The exhibition is made up of original prints from the collections of the SIP and the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, and fills two small galleries. It is organized not by artist or geography but by the ideas the photographs confront: the eye; nightmares; dolls; mirrors; women.

Vered tells me that visitors are often surprised by the work. Striving to undermine the perception of "direct vision," surrealists played with photographic processes to create images that are unnerving and illogical. A work like Nathan Lerner’s photomontage "Eye in Mouth" shocks visitors with its unlikeliness. "People have the concept that photography was always "true" before Photoshop was invented," she says.

I notice that women are as often the artists of these photographs as they are subjects, so I ask Vered if she sees a difference in their portrayal by male and female surrealists. She shows me two portraits: James Hamilton Brown’s "Untitled Photomontage" and an earlier image by Dora Maar, "The Years Lie In Wait for You". Each depicts a woman’s face obscured—Brown’s by fine spirals, Maar’s by a spider’s web. The images are striking in their alikeness. To Vered, this represents what a woman was to the surrealists—the "femme fatale": mysterious and unreachable. Both men and women, she says, bought into this single idea.

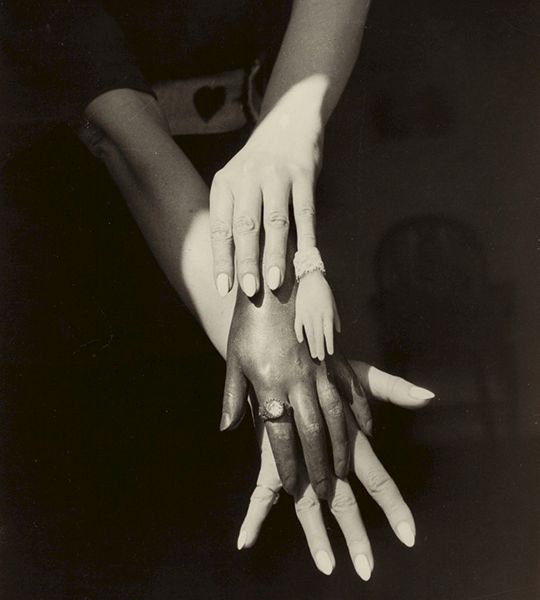

There is one exception: an untitled image depicting four hands layered one on top of the other. The little finger of the manicured top hand becomes the arm of another, small and plastic, the hand beneath them darker, life-size but also artificial. The work is by Claude Cahun, born in France as Lucy Schwob, who gave up her name in favor of one that didn’t mark her with a gender. The image is beautiful, weird and complicated. "This is my favorite work," Vered tells me.

The photographs in the exhibition are like old letters: they are a way to find something out but they are not the thing to be found. They feel not like relics from the past but part of an ongoing conversation—living and urgent; questions without answers.

Off the galleries there are other doors: locked. One has a panel of glass so I can see into the rooms beyond it, and I catch a glimpse of an office, a cabinet with thin drawers for storing prints. This is home to the rest of the Shpilman collection—over 900 works—and where the curators do their research. As I step outside, the streets have changed color. Eritreans leave their churches dressed in white. The robes of the women stretch past their feet, trying to reach the earth beneath them.

Lara WeekThe Melbourne-based Lara Week is a designer for theatre and dance, and associate producer for international arts lab Tribal Soul.

All images via: Shpilman Institute for Photograhpy. Exhibition space by Ariel Caine; Portrait of Shalom Sphilman by Dudu Becher

More Information on Shpilman Institute for Photograhpy