BMW Art Guide by Independent Collectors

Initiating Dialogues

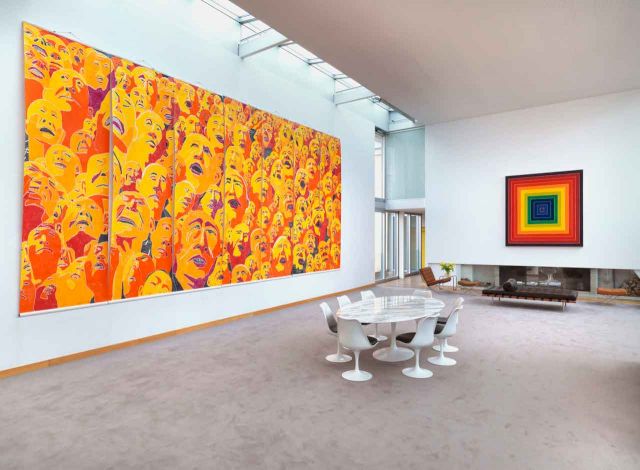

Sammlung Hoffmann – Berlin, Germany

It takes a courageous artist to defy contemporary movements and a courageous couple to invest in works by such artists and then open their home to strangers. Yet this is exactly what Erika and Rolf Hoffmann have done during the last five decades (Rolf passed away in 2001 but Erika has since continued what they began together). After meeting in the early sixties, their interest in contemporary art solidified itself as they visited exhibitions and spoke with artists during the vernissages at the Abteiberg Museum in Mönchengladbach.

“We liked to gain an idea of the artists’ thoughts—how differently they thought about their work, what they considered as problematic in society, all of that,” Erika remembers. “They were very inspiring talks for us. We were building up a company and were hungry for ideas which could lead us a little outside of that professional landscape.”

Early on, the pair met and initiated private conversations with likes of Marcel Broodthaers, Richard Long, and Lawrence Weiner, all of whom now have a place within the Hoffmann Collection. Their first purchase was of a work by the Zero group—comprised of Heinz Mack and Otto Piene—in 1968 and although they began with a focus on European artists (albeit never on a specific movement or location), their horizons soon broadened when they traveled to places like New York for business. There they developed longstanding relationships with artists such as Frank Stella, whose work Of Whales in Paint; in Teeth; in Wood; in Sheet Iron; in Stone; in Mountains; in Stars (Moby Dick Series chap. 57) (199) permanently hangs in their Berlin home.

Stella’s work is an exception to the 1 200 artworks in the collection, which are rearranged every summer. Public audiences can enter Erika’s home every Saturday for a guided tour—an idea that entered the couple’s mind when the Berlin Wall fell. At the collapse of the GDR, they desired to share their collection with those who had been deprived of contemporary western art. Visitors could all of a sudden view works by pop art icons like Tom Wesselmann’s Nude Banner (1969) and Great American Nude #74 (1965), or Andy Warhol’s Sunsets (1972) and Electric Chair (1971).

Despite some of the immediately recognizable names, the Hoffmann Collection has always followed the collectors’ personal interests, ignoring market pressures or trends. They have searched for artworks and artists who aren’t afraid to swim upstream, against the status quo, and in doing so offer continuous inspiration. “We wanted to be challenged in an intellectual and emotional way, so we shied away from works we found too easy or too beautiful,” Erika explains. François Morellet’s Peinture (1952), for example, still holds the same power for her that it did when they acquired it.

“It’s a tiny wooden board with seventeen parallel green lines. There could be endless lines, like going around the whole globe, yet you are just looking at a tiny detail of the cosmos that this painting evokes,” she says.

Emily Mcdermott is a writer and editor based in Berlin.

All images courtesy Sammlung Hoffmann, Berlin, Germany

More Information on Sammlung Hoffmann