BMW Art Guide by Independent Collectors

Reflection and Speculation

Sammlung von Kelterborn – Frankfurt, Germany

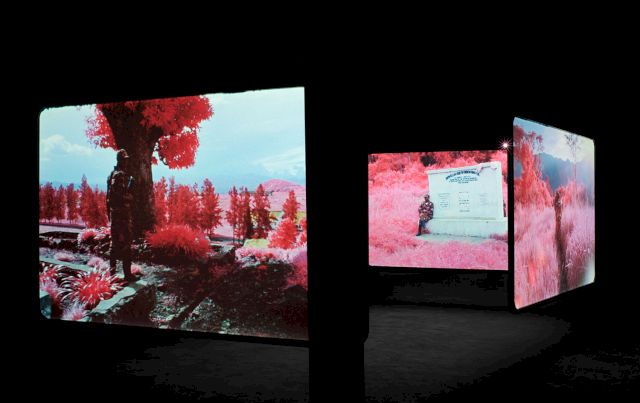

The von Kelterborn Collection isn’t for the faint of heart—although that’s not to say the works are visually jarring. Rather, the artists in Mario and Julia von Kelterborn’s collection draw in viewers with their objectively beautiful and intriguing aesthetics only to give way to a much deeper, often intellectually challenging, message. Take, for example, Richard Mosse’s The Enclave (2013), a multi-channel video installation. Made with 16mm infrared film, the six videos playing in the darkened space at first appear like something from a fairytale (brilliant crimson, lavender and pink flora; stretching, mountainous landscapes populated by only a few roaming figures), however, during the work’s nearly forty minutes, unsightly scenes and sounds reveal themselves: bombs explode; soldiers march with guns; a man is found dead—or at least severely injured—on the ground. Mosse’s films, despite their radiant coloring, are documentary footage of the Congo’s ongoing humanitarian disaster in which, since 1998, more than 5.4 million people have died. “As Mosse and other people say,” Mario reminds us when we speak over the phone, “Beauty is the sharpest tool in the box.’ If you show people something beautiful, they react.”

Mario, who was born in what was East Berlin and has lived in Frankfurt for more than twenty years, first saw Mosse’s installation during its debut at the 2013 Venice Biennale, where he immediately knew he had to leave the Giardini and, if he could afford it, buy the work. “The same happened with Hito Steyerl’s Factory of the Sun at the German Pavilion,” he admits. This instinctual, guttural reaction—what some might deem an irrational decision-making process—is precisely the way he and his wife have developed their collection, which now comprises an impressive array of works by contemporary international artists who often deal with political topics and work in photography and video, such as Mosse, Steyerl, Harun Farocki, Tobias Zielony, Barbara Klemm and Taryn Simon. Mario explains that his specific interest in filmic works may stem from his intense relationship to television and cinema while growing up in the GDR, but also that video works are easily democratized. Single-channel videos are, he notes, essentially free to send to an exhibition and require little more than a projector and screen for display. And while works like The Enclave and Factory of the Sun are much costlier to install, they can be exhibited in more than one place at the same time.

“As a collector, you’re taking on a big responsibility, especially with video or video installations. You need to show these pieces,” Mario says. “So I’m not thinking about whether or not an artwork would work at home. I think of it in an institutional context, and that is the biggest pleasure of all: To think about putting the artworks together and making an exhibition.”

Although one must wait to exhibit until a collection is large and strong enough to tell a story, the von Kelterborns didn’t find this difficult. After Julia introduced Mario to the worlds of modern and contemporary art in the 90s, collecting came naturally, because, as a child, Mario was an avid stamp collector focused on the era of German hyperinflation in the 1920s. He researched and discovered mistakes, amassing a stamp collection that eventually told a historical story and could be exhibited. This dedication and specificity, as well as the ability to see the bigger picture, now reflects his approach toward art. To Mario, art and stamps are both kinds of time capsules. “The only difference is that stamps were mostly for history and while art teaches you about history, it also teaches you about how people interact and what is happening today,” he says.

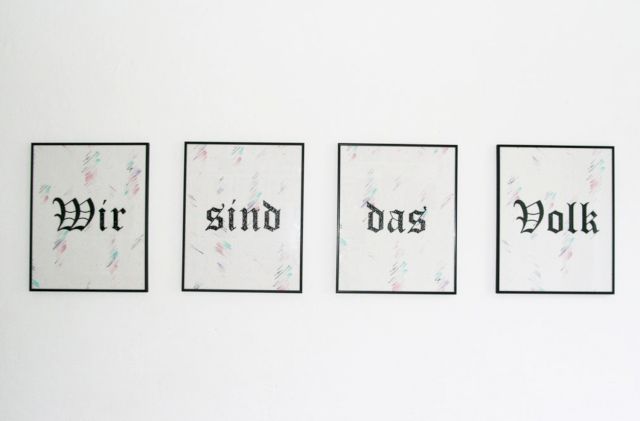

A piece like Henrike Naumann’s Four Words (2015), which spells out “Wir sind das Volk” (We are the people), for example, simultaneously reflects German history and allows this specific phrase to infiltrate new contexts, thus creating a narrative of its own. With works that almost all act in this manner, The von Kelterborn Collection reflects, teaches and speculates about tangible and intangible histories, and, perhaps more importantly, histories-to-come.

Emily Mcdermott is a writer and editor based in Berlin.