BMW Art Guide by Independent Collectors

ANNE & WOLFGANG TITZE COLLECTION

A Lifelong Love Story: How Anne & Wolfgang Titze Built a Collection That Reflects Their Passion, Journey and Vision

The collecting activity of Anne and Wolfgang Titze, which began thirty years ago, was initially driven by a fascination with the iconoclasm of the 1960s, which revolutionized the entire art world. Originally motivated by the American Minimal Art movement, the collection soon expanded to Europe — particularly through Nouveau Réalisme in France, the ZERO Group in Germany, and Arte Povera in Italy. Later, it also included the Gutai Group in Japan. Exactly 15 years ago, a strategic decision was made to enter the realm of figurative art as well. As a result, the collection is now capable of fully conveying the complex development of art over the past decades, achieving a professionally and systematically curated museum-quality standard. Today, it is the collector couple's wish that their collection will continue to shine beyond their time - through the "Anne & Wolfgang Titze Foundation" as a living testimony to their shared vision and inspiring complicity.

In conversation with curators Mario Codognato, Severin Dünser, and Luisa Ziaja, Anne and Wolfgang Titze shared their personal approach to art, how they have shaped their collection, and the themes that resonate throughout their works. These reflections provide a deeper understanding of their passion for art and their distinctive vision as collectors. This conversation took place on the occasion of the catalog for the exhibition Love Story – The Anne & Wolfgang Titze Collection, which was on view from June 15 to October 5, 2014, at the Winter Palace and the 21er Haus (now Belvedere 21) in Vienna. The exhibition presented a unique selection of contemporary art from the private collection of Anne and Wolfgang Titze, exploring the intersection of minimalism, emotional expression, and the connections between historical and contemporary works.

[...]

Wolfgang Titze (WT): I would never have started this adventure without Anne. We fell in love together. We fell in love with art, and we entered the art world together. Our title Love Story is about focus. It is a fascinating exercise to develop a focus and try from the beginning not to deviate from it. We collect art as a passion. Art binds us.

We once read that “collecting often begins with a personal affinity for one object or idea.” Most people start collecting something, even art, at an early age. Did either or both of you collect anything? Did that influence you later in life?

Anne Titze (AT): I recall collecting small objects, remembrances of places, people, moments, memories – a piece of the Berlin Wall, a bullet that grazed my leg in Angola, a colonel’s military badge, pipes from an Indian tribe on the Amazon river, ashtrays from French foreign legionnaires. Everyday things, like the objects that intrigue Gabriel Orozco. Later, I started a collection of French colonial painters, from Africa and Asia, with the first money I earned. I still own a naïve, but strong, colorful painting of a Senegalese warrior posing stiffly with his lance, and also a big painting of a Vietnamese couple sitting in the rain on a junk in the Halong Bay. The art I bought was related to my professional life and exotic trips. But I really started to look at contemporary art early in the second part of my life with Wolfgang.

WT: I never really collected anything. An aunt gave me a collection of stamps, but it never evolved into a passion. Our house manager in Provence built a shelf for my sports trophies in our garage. I really dislike it. The trophies are souvenirs and memories that are lined up like a Haim Steinbach sculpture.

Did museums or galleries play a role in your life, either in childhood or later?

AT: I cannot remember visiting a museum with my parents. They were busy with their own interests. I graduated in history from the Sorbonne. So, when I was older I was always more interested by political and social issues from the 17th century until today, rather than art. And yet I was and am a very visual person.

WT: After the war, our parents took their young children to the Viennese museums, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in particular. My father was a cartographer by profession. He was a brilliant autodidact in many fields: painter, actor, and philosopher. He loved the 19th- and 20th-century masters especially. But I vividly remember how boring it was for us to stand in front of a Titian or Rubens listening to my father’s lectures. I am grateful today. His lectures gave me my first approach and connection to, if not understanding of, contemporary art.

You are global citizens, and your collection seems to reflect both of your different personal and professional backgrounds.

WT: We have always been connected with the world. For years, I flew around the world as a business consultant – from Europe to Asia to South America – meeting business people and politicians, absorbing and synthesizing information, and trying to help solve the problems of the world.

AT: Early in my career, I had more exposure to people from the Third World. My first gig was in Angola. I traveled everywhere, including the Eastern Bloc and the Soviet Union. I produced many stories there and loved the mood, even the feeling of being under surveillance, spied on, like many news reporters. I met a lot of shadowy characters, dissidents who were putting themselves in danger by meeting us.

Is art a common language for you both?

WT: When we met, Anne and I spoke English with each other since we did not have the same native tongue. There are two languages that do not need any translation: music and art. We found art together. It became part of us as a couple, a common language that helped our communication.

How did you begin your Love Story with art?

AT: The first work we bought was a diptych by Klaus Rinke. It was a homage to Matisse that looked very contemporary and was easy to understand.

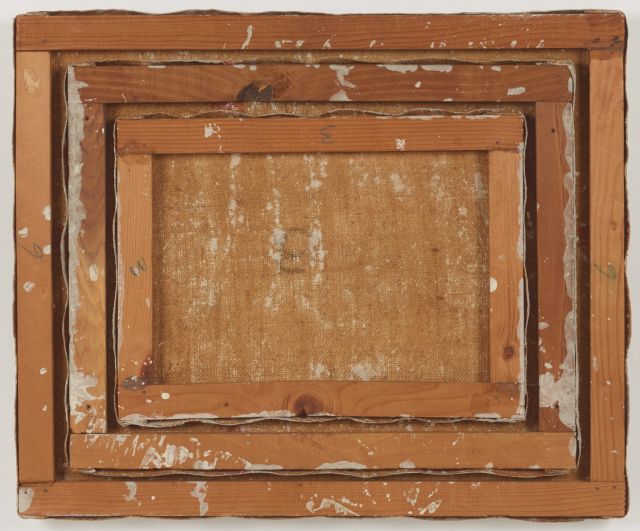

WT: About the same time we began buying Austrian art: Nitsch, Rainer, Graf. They were connected with the 60s and with my youth. But we did not buy these artists as collectors. We started as people who were interested in art, but we had no real vision and certainly not the desire to become collectors. We wanted to live with art. You start to live with art when you put it on the walls. I do not mean decoration. Never. Actually to the contrary. We sometimes had to remove furniture or carpets to let the art breathe by itself.

Who followed the Austrian artists?

WT: In 1989 we met Liliane Vincy, the Parisian gallerist, who opened our eyes and gave us access to the art world. She made us aware of the French Nouveaux Realists: first, Arman, Hains, Klein, and Rotella. Later she introduced us to Arte Povera, with Penone, Paolini, Merz, and Kounellis. Vincy’s passion for and knowledge of these artists was amazing. She also knew them all personally. She was a very good teacher, and she shared with us her love for great artists like Fontana and Manzoni.

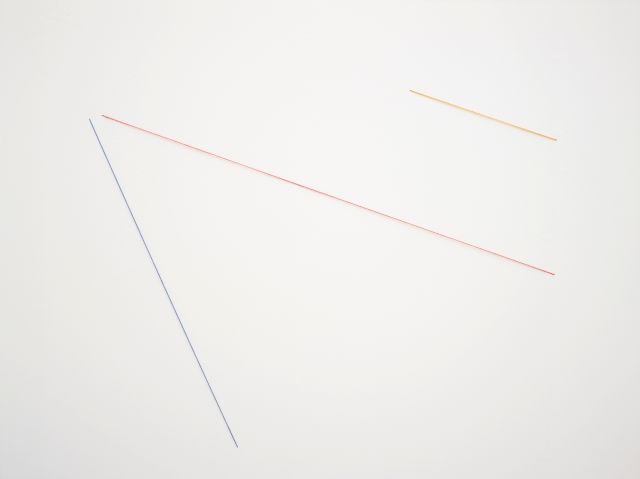

Minimalist art, especially American Minimalism, has a very important place in your collection. Who led you there?

AT: Bernar Venet, the French sculptor, is the husband of my very good friend Diane. He was extremely influential in our discovery of Minimal art. It is art we did not understand. To be honest we looked at it reluctantly. We had a sort of contempt for the snobs who could look at, admire, and even buy this dry and unappealing art.

WT: Bernar always loves to tell the story of our first visit to Le Muy, his extraordinary estate in the South of France, where he shows his sculptures and the couple’s private Minimalist collection. We were standing in front of a Robert Morris felt sculpture. We were bored. We were lacking patience, and we had already had more than enough from looking at Judd, LeWitt, Flavin, and Stella. We said, “No, Bernar. Impossible. This old brown decayed piece of rug cannot be art!” Bernar, with his inimitable way of sharing his dedication to art, was our eye opener. He initiated us. Then we started to read about and look at Minimal art on our own. It was the beginning, the core of our collection. We have never stopped looking at Minimalism and adding to our collection.

What was the first piece of Minimal art you bought?

AT: Donald Judd’s Untitled, 4 pieces, 1982. It is in the 21er Haus part of the exhibition. It is an extremely personal work. Judd made it for Bernar Venet. Bernar was living in New York, and became friends with Judd and many other artists like Chamberlain, Flavin, LeWitt, and Stella. All of these friends are now in our collection. They are together.

WT: Because of Bernar and this piece, we developed the collection into this direction: steadily, constantly, and together. It became glue in our relationship, our mutual construction.

Did that lead to your interest in Conceptual art overall?

AT: Like Minimal art, Conceptual art in general isnot beautiful at first sight. It gets beautiful, butyou need a boost. Most of our friends always say,“Yes. Okay. We understand that Conceptualart is important as a historical art movement, butdo not say that you are emotionally touchedby this art.” They have never read Sol LeWitt’s “Sentences on Conceptual Art.” He lucidly revealsthe beauty and the humor, the fact and fancy.

WT: We are both touched by this work. WhenI look at our Minimalist art pieces, it touches me in my head, in my heart, and in my belly. It is the same for Anne. Art, like music, cannot only come from or appeal to the brain. You have to feel it. Schoenberg, Webern, and Berg are not easy to listen to, just like Judd or Flavin are not easy to look at. You grow with the music and the art.

So the idea of titling your first exhibition, Love Story, connects with that? It relates to your feelings as a couple and toward the art?

WT: Yes, it is our love story. Like we said earlier, collecting is a journey we have taken together.

AT: Actually, for me it has been an endless trip through the artists’ worlds, and this is reflected in the collection. We started with other artists, not the Minimalists. At first we purchased some of the Soviet bloc artists, like Eberhard Havekost and Wilhelm Sasnal. Both of these artists came from behind the Iron Curtain, a world I knew very well. Havekost’s green-yellowish painting, Augen (Eyes), with a line of old cameras pointed towards the people, is at the 21er Haus, right at the museum’s entrance. It looks like a threat that was always present. It still is.

How do you participate in the art world? Today’s art market seems very complex, with galleries, fairs, museums, exhibition places, and social media?

AT: We are very selective. We do not visit all the art fairs, only the main ones. We will probably add Hong Kong next year. But we usually visit a familiar set of galleries that we like: American, English, German, and French. We follow their artists and are introduced to new ones. Of course we visit all the museums whenever we visit a city or country. As for social media, “bof, bof.” That is French for “whatever.”

Do you connect personally with the artists as friends?

AT: With few exceptions, I prefer not to meet artists and do studio visits. It creates an unnatural pressure. At the end of the studio visit there is always the underlying expectation or question: “Are we buying or not?” If not, I feel that I have wasted the artist’s, consultant’s, or gallery’s time. I feel more comfortable having a gallery or consultant screen the art to avoid uneasiness and potential misunderstandings. This is particularly true for young artists. I prefer to read about artists and their art or look at a documentary. I get a full picture of them and of their works without intruding in their lives. I feel the same way about meeting writers or filmmakers. Some artists may be great, but not articulate or emotionally strong enough to talk about their work. I recently met a well-knownartist at a dinner party, and I asked him, “Do you like to meet collectors?” He answered with a very flat, “No.” I loved his honesty.

WT: Okay, now we have a lover’s spat in our Love Story. But it is a skirmish, not a war. I do not expect friendship with an artist, and I do not care if we develop a kind of mutual interest. But talking to artists is so important. Here is a good example. If we had not been to Sterling Ruby’s studio, we might not have bought his work at all. I understood the way he collects objects on the streets of LA, how he makes his collages, how much he has been influenced by graffiti artists and even gangs. This is so LA. We had the same experience at Nathan Hylden’s studio. Three hours of explanation on the process of making a painting is hard listening. But this new approach was very fascinating to me. Personal contact brings more.

Aren’t you curious about artists’ personalities?

AT: Not very much, honestly, but there are exceptions. I like artists who have fragility, with ups and downs, including black holes. I have met artists who obviously were “suffering” at meeting us. It can be very challenging for them and for me as well. I felt Fred Sandback’s uneasiness about meeting us in New York in his Broadway loft. His wife had to do all the talking. I felt that he wanted us to be somewhere else, to leave him with his art, with his family, with his cat. I felt like an intruder. Not Wolfgang, the consummate consultant, my arbiter. Of course this changed when Fred and Amy came to our house in Provence to do an in situ sculpture. We spent almost a week together, and had the time to build a personal relationship. It was wonderful. Fred sort of opened up, and he was so relieved to see that he could deliver a sculpture we immediately loved.

WT: With the artists, I discover a totally new world. If you meet artists, they mainly reflect their works. They reflect the art. Shirazeh Houshiary, it is she. It is her sensitivity and mystical poetry. Sterling Ruby too, with his khaki trousers and long hair. The day we met him, he had two broken teeth, looking like a homeless Angeleno. Now, we have learned, he collaborates with the fashion designer Raf Simons. In consulting and finance, I never met people like artists. The gray suit and white shirt is a conformist uniform that makes everybody look alike. People are rather predictable.

Do you like meeting with other collectors?

AT: To be honest, it is not a priority or focusfor me.

WT: We have met a lot of interesting people from all over the world. Nevertheless, we do not collect collectors.

Returning to the question of art collecting, your collection is focused upon contemporary European and American art. Was this a conscious decision, or did it just happen?

WT: We always said that we could not collect everything. When we started, we looked at art everywhere, all over the world. The circuit of galleries, fairs, museums, and private collections is endless and informative. We looked at all art movements, including Pop art. We decided to focus on Minimal art and then on the post-Minimalists, the artists who followed in their footsteps. We also looked at contemporary Chinese art, and were very interested by the artists from emerging countries. But we stuck to our primary interest. We made a detour, an exception, with Indian art, and gathered an interesting collection of prominent Indian artists from Subodh Gupta to Barti Kher, TV Santosh, Rachid Rana, and Ryas Komu, and more. We stopped for two reasons. We were uncertain by the way they developed, and shocked by the disastrous market speculation that quickly followed them.

AT: This is all true. I can also add that as a television producer I covered many stories on women’s issues from all over the world. It is no wonder that we were keen to discover and collect many women artists, like Agnes Martin, Sarah Lucas, Rebecca Warren, and Lisa Yuskavage. They push beyond the female border, the female identity.

How do you add an artist to your collection?

WT: We try not to add too many artists because of our focus. When we are keen on an artist, we try to collect the work in depth. I like steadiness and consistency in an artist’s development and direction.

AT: Wolfgang and I talk for hours about a new artist joining the collection. Hours. It is both exciting and stressful to judge an artist’s work and then decide yes or no. We are trying to be selective, but it is difficult.

Do you always agree or reach a compromise?

AT: Nigel Cooke and Dirk Skreber are good examples. I took the lead on these two artists. I love Cooke’s post-punk despair, the way he paintsand talks about artists, drunkards, and bums, including himself. I think that Skreber is one of the best contemporary German artists of his generation. Again, I love his universe, his wit, the constant threat and anxiety he conveys through his art. It is uncomfortable. Wolfgang reacted instantaneously and positively to Sterling Ruby and Nathan Hylden. I followed quickly.

WT: I needed more time with Nigel Cooke and Christopher Williams, for example. We have friends in Princeton who were and are fans of Williams. I thought it was cold, dry. Then one day I saw a work at a fair. I got it. Our friends said they had thesame experience. They also had a Williams epiphany.

Can you give us an example of your “in-depth” pursuit of an artist’s work, and of the discussions you have had?

AT: We have many works by both Cooke and Skreber, but I had to defend their work, in my interaction with Wolfgang. This is a good thing. It forces us both to consider the work with rigor, not just emotion. We do not simply judge physical beauty, but also how it makes us think and feel.

WT: Dan Flavin was an artist I advocated. Anne was reluctant to add his work to the collection because of her aversion to fluorescent light. She said it was a nightmare for a filmmaker.

Are there specific artworks you would love to have?

AT: After years of looking at art, we could readily judge the difference between an “A” and a “B” grade work of art. When we were not offered the best pieces, we skipped the offer. It was sometimes painful to say no to an artist whose work we would have loved to collect, but we wanted to have top-notch work.

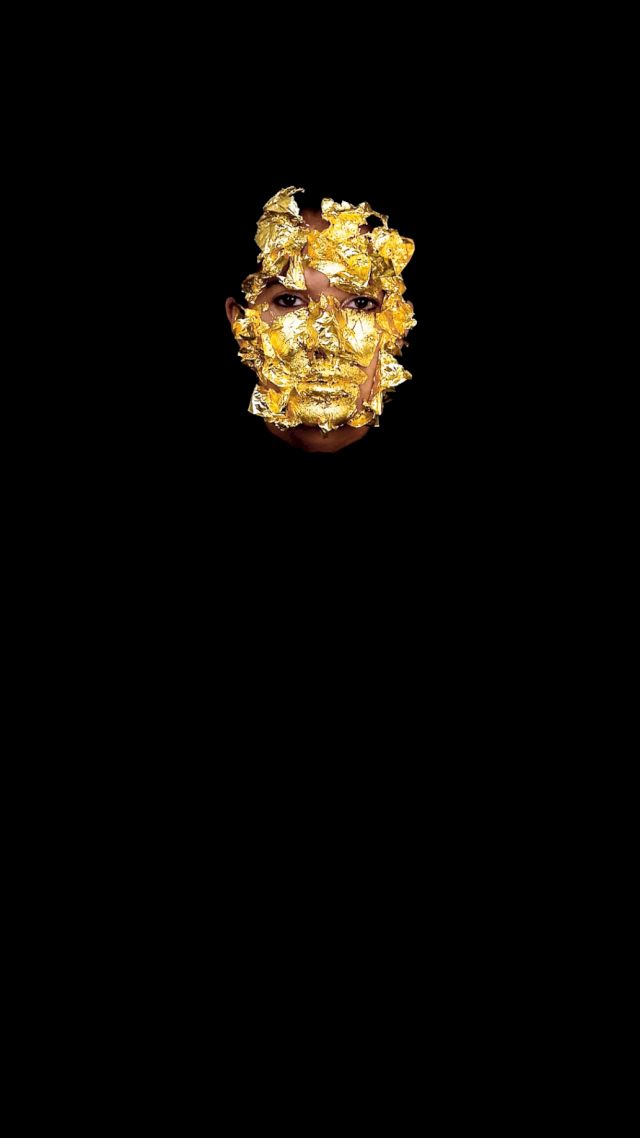

WT: Rudolf Stingel is a good example. There are four works in the exhibition at the Winter Palace. We started to collect Stingel very late. It was and continues to be difficult to get a portrait or photorealistic painting.

AT: Also, sometimes we said “no” because an artist we loved was not in the line of our collection. Years later we regretted some decisions. We have tried to keep our focus. It is not easy.

WT: It can take years before you can buy the best pieces by an artist you want to collect. Galleries offer the works first to museums and private foundations. Or, the galleries sell them to their best clients or to new and more glamorous so-called “collectors.” We are also big lenders of art. We have never turned down a museum, from Japan to Mexico to Vienna, for an exhibition or a retrospective. That helps our relationships with galleries and the artists. We had to work and pave our way forward with galleries and artists, proving that we are serious collectors. It takes time, and it is often frustrating. The galleries know that we do not sell work, especially the young, hot artists who are the darlings of the market and the auction houses.

Are you suggesting that it is difficult to collect contemporary art?

AT: Yes, it has been a long and difficult process, developing a sense of judgment and good eyes. It is even more difficult for young collectors today than it was for us. Personally, I feel that I earned the respect of my profession in a few years, but after many years in collecting I sometimes still feel insecure. I ask myself, “Do I have the knowledge of what a good piece is? Am I not too enthusiastic? Are we given enough time to think about the artwork?”

WT: When we started collecting art, we were told that there were a small number of collectors. Our Princeton friend teaches art market economics at NYU. He says there are about 150,000 to 200,000 people in the world who are the foundation of the contemporary art market. Today there are hundreds of wealthy people – bankers, hedge fund managers, equity investors – as well as millionaires and billionaires from the emerging countries who have entered the market. Most have short attention spans. And then there are the speculators. When we bought Silverheels, our historical Chamberlain sculpture, the price was very high at the time, but we had almost a year to decide about the purchase. Would we be able to get it today? If we were lucky, we would have two hours at most to decide.

So, are you specifically talking about market conditions?

AT: Some of the exhibitions of high-demand artists are sold out very quickly. Some buyers buy the entire exhibition. It does not give other collectors even a small chance.

WT: It has always been an intellectual challenge to collect, but now there is an additional stress factor. You have to fight for the best pieces, and you have to make your decision very quickly. At a fair you sometimes have a half hour to decide to buy a piece. Art fairs are not exhibitions and not vacations. They are hard work. We get offers in advance, so we know what is being brought to Basel, London, or Miami Beach. We may reserve work. But the decision time is short, almost instantaneous.

Have you ever been discouraged to the extent that you wanted to stop collecting?

AT: We had the temptation some years ago to give up collecting, telling ourselves that it was no fun any longer and that the art world had become too focused on money. We said, “Let’s just enjoy concerts, films, theater, or museums.” Art has prevailed because we love the ongoing intellectual challenge connected to it.

So you make a distinction between buying art and being a collector?

WT: Collecting is about having a goal and a vision. Some collectors even say that the work of collecting is more important than the work of the artists. Of course this is not true. Collecting is entirely different. Still, collecting is a creative, conceptual, and visionary act, especially if you do not have unlimited funds:

AT: What we also like about collecting is that it reflects our personalities, our sensitivities, and our tastes. It is about the issues and interests of our generation, and the next one. For example, we are very interested in getting more familiar with the works of the process artists who use today’s technology. Personally, I must say that sometimes I do not understand what these younger artists are talking about, but I love to look at the final result. Some of them may be experimenting with new technology and making beautiful works. Others, like Tauba Auerbach, have reverted to a centuries-old craft – weaving.

WT: An artist’s work is a portrait of himself, and it is the same with a collector. In our case, the collection is a portrait of both of us. We have found our way this far, and we can say, like the artist Claude Lévêque, “Nous sommes heureux!” We are happy.

Is the collection a portrait of a Love Story?

AT: We have changed a lot during these 20 years. At the beginning, looking at art, we were driven more by our intellect. At least I was. We were keen to put together words and explanations about the works we were looking at, especially Minimalism. Today I am returning more to emotions. I want to have an immediate feeling in front of an artwork. To have a “coup de foudre,” you know, love at first sight. I still remember the revelation we had in front of an Agnes Martin. It was a fist in the gut. Time and again I ask myself, “Do I love this painting or not? Is the message substantial or not?” I am less and less sophisticated in my approach to art. I let the passion come through. I rely more on my eyes and feelings than earlier.

WT: Here I differ with Anne. Of course, having started collecting Minimal art, it has been an intellectual exercise. How do you want to understand the 60s and 70s without having a key? For me, through understanding these artists, I developed certain emotions. If I look at our Judd, I feel the same thrill as when looking at a Manet or a Monet, maybe more. When I look at the young process artists, I understand them, but I also need an emotional click. I am trained so that I can combine the two things. Anne is more on the emotional side right now, so we talk about it very much. Like we said before, it can take hours to make a decision.

Love Story seems to have several plots and subplots, like a Hollywood movie. Is there any conflict?

AT: Sometimes people ask us how we can love the works of Donald Judd and Lisa Yuskavage, and even commit to buying them both. They are so different. The answer is that we love to wander around, to take different roads, and even to get lost. It is an evolving script.

WT: Ten years of collecting is the minimum required to understand art and to buy the right pieces. We are still making mistakes, sometimes on judging the artists, but less in choosing their works. And yet that is not the right word. Art is not a mistake. You have to learn for yourself and rely on your judgment. The plots and subplots fit together in a more understandable way. Our goal today is not to add numbers to the collection, but to focus our collection on the best.

How do you see the future of your collection?

WT: First, we will continue to collect together. (Laughs.)

AT: I cannot imagine continuing to collect without you, Wolfgang. What did Alain Badiou (the French philosopher) say? “Love without risk is an impossibility.” It takes a long time for a strong, opinionated couple to cooperate and adjust to each partner’s perspective.

WT :We bought Sterling Ruby almost at the beginning of his career. We saw a spray painting, and I thought: brilliant! It is the same thing with Wade Guyton. We did not understand clearly what his work was about, but we bought the white painting because we felt it was beautiful. We looked at a lot of young artists. When we are not sure, we tend to wait and take our time.

Do you feel a responsibility to show your collection?

WT: I really believe that art cannot be a private asset. Art belongs to the world, like music and literature. The wonderful thing is that in time the finest works find a home in museums. It might take a few generations, but there always comes a time when the heirs sell. They may need the money, or they may not be interested in keeping the collection. Collections end up in public spaces. This is good.

AT: We never felt strongly that we own this or that piece. Yes, of course it is part of our personal effects or assets, and it has a value. But we see collecting as a transitional home for the art. Collecting is caretaking. We have the privilege of looking at the art on our walls, but we lend art whenever we can. Paintings or sculptures regularly disappear for months or years. In a sense, we have given it away to the world, like pushing a fledgling from the nest.

Will you build a private museum or give your collection away?

WT: We thought about it for many years: first Paris, then Vienna. Finally, we decided against it. We spend so much time collecting that having a museum would mean that our lives would be devoted to it. We have too many other interests. Also, having a museum is no different from running a company. I have done too much of that in my life. Our professional careers were accomplished and fulfilled. Why have another one? We do not have to put our names on the top of a building or on a business card. From the beginning, there was no question that this collection would end up in museums. I have such a respect for art. You cannot own it like a car. Ideally, we would like to keep the collection together. But perhaps we will distribute it among several museums, with one museum getting the Minimalists, another one the Arte Povera, et cetera.

Will this exhibition be something you will do just once, or are you planning to do more?

AT: For me, this is a unique occasion, especially in Vienna at the Winter Palace and the 21er Haus. We feel totally in tune with the curators, with the two spaces, one being in the historical center of Vienna, the other one in a part of town linked with Vienna’s future. I do not know if this particular presentation could be repeated again with the same style.

WT: For me, the time has come where we have to be more public. We have been approached several times by museums to exhibit our collection, but this opportunity in Vienna seemed to be the best for the collection and for us. If some museum comes to us and wants to show our Minimal art collection, for example, we will do it and support it. We will open our collection and it will have more exposure. This should be our goal.

AT: For me, this exhibition is the peak of 20 years of collecting. I have enjoyed the total carte blanche that the museum and its director, Agnes Husslein-Arco, have given us. I love the freedom we have had to express our views in choosing and displaying the works.

WT: The Winter Palace is such an incredible place. Where else in the world are you being given such a space? It is an enormous privilege. We immediately said, “Yes!” to Agnes Husslein-Arco. We did not even think of feasibility, we thought of possibility. Agnes Husslein-Arco offered to expand the show to include the 21er Haus. This presented a totally new dimension, and let us make a real portrait of our collection, our Love Story.